SEPTEMBER 19, 2020 BY PAUL LOUIS METZGER

In “Conspiracy Theories: In Pursuit of Truth,” I claimed that New Testament Christianity may have been a conspiracy theory movement. I made that claim based on a certain definition of “conspiracy theory.” To repeat that definition, political scientist Joseph E. Uscinski, an expert on the subject matter, defines conspiracy theories in a video recorded interview as follows:

A conspiracy theory…is a[n] accusatory perception in which a small group of powerful people are working in secret for their own benefit against the common good and in a way that undermines our bedrock ground rules against the widespread use of force and fraud. And further, this perception has not been granted legitimacy as true by the appropriate epistemological experts with data that is open to refutation.

Again, based on this definition, New Testament Christianity may have been deemed a conspiracy theory movement. But that does not mean New Testament Christianity was false. As noted in the prior blog post referenced above, some conspiracy theories turn out to be true, as in the case of the Watergate scandal.

In what follows, we will seek to show that the New Testament community did indeed adhere to what may be deemed a conspiracy theory. We will also sketch out how the church sought to gain legitimacy as being true. Let’s begin with the Apostles Peter and John standing before the Sanhedrin, as recorded in Acts 4. The authorities arrest and threaten them based on their having caused a commotion by healing a lame beggar and preaching in Jesus’ name (Acts 4:1-22). Certainly, the Sanhedrin and Rome would try to silence and terminate the fledgling though quickly growing church given the risks it posed to their established ways.

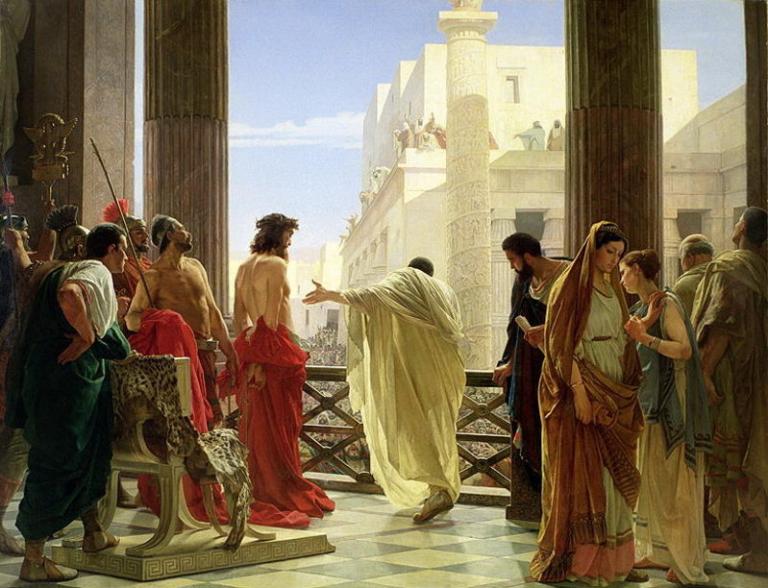

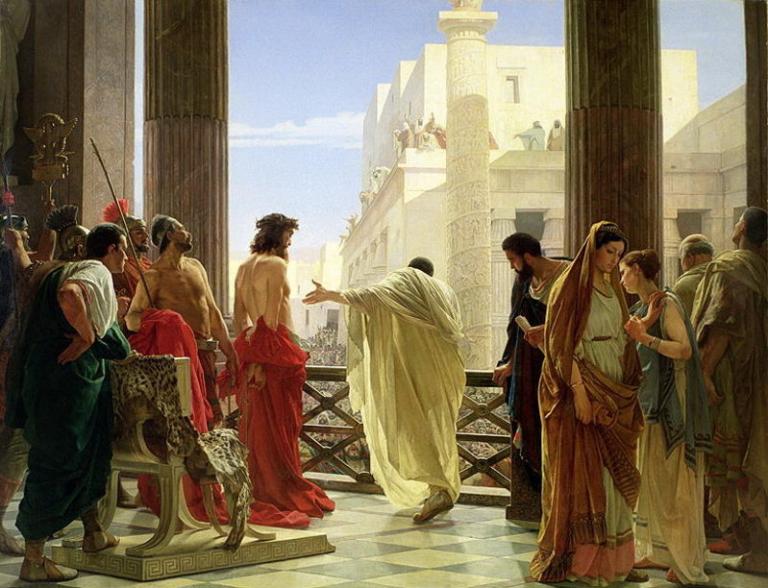

According to John’s Gospel, the same fear of risk to the establishment existed prior to the governing authorities conspiring to kill Jesus. In the face of the threat to their honored status and national security, they determined to seek Jesus’ death:

“…If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and take away both our place and our nation.” But one of them, Caiaphas, who was high priest that year, said to them, “You know nothing at all. Nor do you understand that it is better for you that one man should die for the people, not that the whole nation should perish.” He did not say this of his own accord, but being high priest that year he prophesied that Jesus would die for the nation,and not for the nation only, but also to gather into one the children of God who are scattered abroad. So from that day on they made plans to put him to death (John 11:48-53; ESV).

Back to Acts 4, later upon release from custody, Peter and John returned to the church and shared all that had transpired. Upon hearing from Peter and John, the community raised their voices in unison as they quoted and expanded upon Psalm 2:1-2. The church did not see themselves as a counterfeit organization. Rather, they interpreted the actions of the rulers and authorities as a conspiracy against the Lord and his Anointed, and that Jesus’ followers were the faithful remnant:

Sovereign Lord, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and everything in them, who through the mouth of our father David, your servant, said by the Holy Spirit,

“‘Why did the Gentiles rage,

and the peoples plot in vain?

The kings of the earth set themselves,

and the rulers were gathered together,

against the Lord and against his Anointed’—for truly in this city there were gathered together against your holy servant Jesus, whom you anointed, both Herod and Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and the peoples of Israel, to do whatever your hand and your plan had predestined to take place. And now, Lord, look upon their threats and grant to your servants to continue to speak your word with all boldness, while you stretch out your hand to heal, and signs and wonders are performed through the name of your holy servant Jesus.” And when they had prayed, the place in which they were gathered together was shaken, and they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and continued to speak the word of God with boldness (Acts 4:24b-31; ESV).

It is interesting to note that the NIV translation of Psalm 2:1 reads that the nations “conspire.” The footnote claims that the Hebrew is best rendered as “conspire” whereas the Septuagint translation into English is “rage.” The NIV translation of Acts 4:27 also reads that Herod, Pontius Pilate, the Gentiles, and people of Israel in Jerusalem determined to “conspire” against God’s “holy servant Jesus,” whom God had “appointed.”

Let’s pause for a moment to highlight that in no way, shape or form should the New Testament use and extension of Psalm 2 be taken as a form of anti-Semitism. The Acts of the Apostles sees what transpired as a set group of Gentile political and Jewish religious leaders conspiring against Jesus, not a select group of Jewish leaders alone, or the Jewish people as a majority or in their entirety.

Certainly, the New Testament community interpret what happened to Jesus as a conspiracy of a small, powerful and elite force of Roman and Jewish leaders arrayed against Jesus, which in turn would have a negative bearing on the common good. Now while they certainly wished to retain their standing, they may have determined (wrongly) that what was good for them as those in power (Herod, Pilate, and the Sanhedrin) was in the best interest of the people. Regardless of whether they sought to benefit the people and not simply themselves, this small powerful force abused their authority in condemning an innocent man (indeed, the Lord’s Anointed) to death. At least in Pilate’s case, he handled Jesus over to be crucified to be spared from the possibility of Caesar’s wrath (John 19:11-16). Here we find at least two of three of the following criteria in Prof. Uscinski’s definition for determining if the New Testament account of Jesus’ death is a conspiracy: “a small group of powerful people are working in secret for their own benefit against the common good and in a way that undermines our bedrock ground rules against the widespread use of force and fraud.”

Uscinski’s definition involves one more criterion for labeling a theory as a “conspiracy”: “And further, this perception has not been granted legitimacy as true by the appropriate epistemological experts with data that is open to refutation.” As stated in the prior post titled “Conspiracy Theories: In Pursuit of Truth,” a conspiracy theory can be true. However, it must be shown to be true by gaining the approval of “the appropriate epistemological experts.” The Acts of the Apostles seeks to make the case for the truthfulness of the theory that Jesus was/is the Lord’s Anointed, that he was wrongly condemned and executed by a small powerful force that (ill-intentioned or not) impacted negatively the common good, and that he was raised from the dead, thereby demonstrating God’s validation. In view of the same guidelines articulated in the prior post for distinguishing whether a conspiracy theory is true, I argue:

- The New Testament community had to go public rather than remain anonymous and present their views to subject matter experts. The Acts of the Apostles shows that Peter, John, Paul and others were more than willing to make their case to those in positions of authority. Paul himself determined to take his case and the gospel all the way to the Roman Emperor’s throne. The Lord Jesus also spoke publicly and engaged the established rule of Israel and Rome. He did not operate in secret and anonymously.

- The New Testament community had to be open to the possibility that they were wrong and that they would live with the consequences rather than secretly retract or shift their views all the while wrongly refusing to admit mistakes. 1 Corinthians 15:16-19, 32 suggests that Paul was willing to accept the consequences for his very public claims that if Jesus be not raised he and the church were the most pitiful people in existence.

- The New Testament community did not seek to benefit from their claims, but rather served the common good at the risk of great personal loss (1 Corinthians 15:29-31; Romans 8:35-36).

- The New Testament community reasoned and engaged in a civil and non-violent manner (2 Timothy 2:24-26; 1 Peter 3:13-17).

How did Jesus engage the Sanhedrin and Roman governor? How did the Apostolic community engage those in authority and the surrounding society?

- If they’re bombastic, be bombastic?

- If they’re controlling, be controlling?

- No, with meekness, cruciform power, patience, civility, and neighborliness.

- Whether viewed positively (the New Testament apostolic community) or negatively (by the church’s detractors) as a conspiracy theory, the focus was the fruit of the Spirit, compassionate co-existence, public rational and self-sacrificial engagement as loving neighbors that confounded the authorities and convicted as well as captivated the people at large (See the whole of Acts 4-5).

Two passages in the New Testament referenced above reflect the kind of virtuous engagement required of those who wish to show that their Christian conspiracy theory is true, not false, or who seek to correct someone whose ideas, including conspiracy theories, are indeed false:

And the Lord’s servant must not be quarrelsome but kind to everyone, able to teach, patiently enduring evil, correcting his opponents with gentleness. God may perhaps grant them repentance leading to a knowledge of the truth, and they may come to their senses and escape from the snare of the devil, after being captured by him to do his will (2 Timothy 2:24-26; ESV).

Now who is there to harm you if you are zealous for what is good? But even if you should suffer for righteousness’ sake, you will be blessed. Have no fear of them, nor be troubled, but in your hearts honor Christ the Lord as holy, always being prepared to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you; yet do it with gentleness and respect, having a good conscience, so that, when you are slandered, those who revile your good behavior in Christ may be put to shame. For it is better to suffer for doing good, if that should be God’s will, than for doing evil (1 Peter 3:13-17; ESV).

Of course, the criticism of the Christian faith as untrue is not simply a first-century phenomenon. May we who embrace the Christian conspiracy theory today follow the example of the Apostolic community and New Testament instructions as we engage critics. And may those Christians who articulate or critique political positions deemed conspiracies in the present moment follow suit.

- TAGGED WITH:

- UNCATEGORIZED