FEBRUARY 10, 2020 BY JONATHAN MS PEARCE

At the heart of the Nicene Creed are these words:

“And [we believe] in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of His Father before all worlds, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father … .”

As this article on Bible.org points out:

In other words, although Jesus was a fully human person, he also was and is fully God. When we speak of the deity of Christ, we cannot water it down to mean that he was supernatural, or a divine being, or most God-like. He was and is God; but he was manifest in the flesh. This is why he alone is able to redeem us. This is why he is to receive our worship and our obedience.

The article attempts to establish the following:

Jesus Christ is authoritative.

The authority of Jesus is based on his deity.

The Father-Son language is not about an actual father-son relationship – it signifies general reverence.

“Only Begotten Son” means fully divine and eternal, uncreated.

“I Am” language defends these points, equating him with Yahweh.

The authority of Christ calls for devotion.

Okay, so we have a Christological conclusion of the Godhead that is the Trinity, if you are to accept all of this. Let’s do so for the sake of argument.

Peter S. Williams, a friend against whom I have debated at the University of Southampton, and occasional early attendee of The Tippling Philosophers, has written an article “Understanding the Trinity” at bethinking. Let us look to see if he can make coherence of the idea.

The core claim is that though there is but one God, he nevertheless exists somehow as three distinct divine persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit, and that this same same but different claim is coherent and not heretical. That, when the Athanasian Creed states, ‘the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods but one God’ the confusion stems from differing “senses” of the term “God”. Williams sets out:

According to Gregory it is false to say that any member of the Trinity 1) is a creature; 2) has come into existence having previously not existed; 3) has existed without the others also existing; or 4) that the Trinitarian nature of the Godhead is a contingent fact (rather than a necessary fact). …

Dawkins is the sort of critic whom Peter Kreeft describes as finding the Trinity:

unintelligible because they are impatient with mystery and have … an arrogant assumption that what is not intelligible to them at first reading must be in itself unintelligible and unworthy of attention…[11]

This, for me, is key. Let’s get this out of the way early on. The most prevailing theory of the Trinity is mysterianism. This essentially says that, even though the Trinity looks incoherent, we know that it is true; we don’t know how it is true, as this is a mystery, but it is definitely true. The many skeptics, this is a cop-out. This is akin to saying 2+2 = 5. We don’t know how it is true (for it is a mystery) but we know it is definitely true. I don’t buy this. Williams goes on to say that people like Dawkins have a particularly naive understanding of the Trinity and so conclude that it is incoherent, and that this probably isn’t helped by some imprecise terminology used by Christians. I would argue that it isn’t just imprecise terminology that undercuts the idea.

Logically, Jesus is God as well as God the Father being God. Where A = God the Father, B = Jesus and C = the Holy Spirit:

A = B

A = C

A = D

But B ≠ A

B ≠ C

C ≠ D

and so on.

What this means is that if the Godhead has, say, 10 properties that identify it has having the label Godhead (something like this must be the case – it must have identifiable properties or the term ‘Godhead’ is meaningless and has no reference) then we have some issues. If Jesus = the Godhead, then Jesus must have all of these properties. But then Jesus is exactly synonymous with the Godhead. But since Jesus is seen as in some way identifiably different to the Godhead, hence the two semantic terms, this cannot logically be the case. And vice versa. So to say Jesus is fully God is meaningless unless to say that Jesus is a perfect synonym of the Godhead. Which then must apply to all the others. The Holy Spirit to be fully God must fully have these properties too, but then they are all synonymous and not able to be differentiated.

Now, these aspects can’t be fully God if they lack some Godlike/Godhead properties. But what if they had more? Perhaps Jesus had 11 properties, 10 of which belonged to the Godhead. But then the Godhead cannot be part or a subset of the Jesus properties, less than Jesus in some discernible way. Or perhaps Jesus = the Godhead + human body. This is intuitively problematic, such that Jesus becomes a different ‘entity’/aspect with more than the properties of the Godhead. (I shall return to this later.)

Furthermore, The Holy Spirit (HS) and Father must have different properties to Jesus in order to be differentiated as aspects/parts/persons/essences/whatever in order to be identified as such. It cannot be that the HS has exactly the same, no more no less, properties as Jesus because otherwise that would be Jesus (as mentioned before)! In order to say, “That is Jesus and that, over there, is the HS” such that they are identifiable as each person, they must have differentiated properties. But that means, if these properties are properties of being God, that neither can be fully God. The HS cannot have a godlike property that Jesus does not have, otherwise Jesus cannot be fully God. This seems to be the crux.

As wiki states:

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (Lat., trinitas from the Lat. triad, “three”[1]) defines God as three consubstantial persons,[2]expressions, or hypostases:[3] the Father, the Son (Jesus), and the Holy Spirit; “one God in three persons”. The three persons are distinct, yet are one “substance, essence or nature”.[4] In this context, a “nature” is what one is, while a “person” is who one is.[5][6][7]

According to this central mystery of most Christian faiths,[8] there is only one God in three persons: while distinct from one another in their relations of origin (as the Fourth Lateran Council declared, “it is the Father who generates, the Son who is begotten, and the Holy Spirit who proceeds”) and in their relations with one another, they are stated to be one in all else, co-equal, co-eternal and consubstantial, and “each is God, whole and entire”.[9] Accordingly, the whole work of creation and grace is seen as a single operation common to all three divine persons, in which each shows forth what is proper to him in the Trinity, so that all things are “from the Father”, “through the Son” and “in the Holy Spirit”.[10]

…

In 325, the Council of Nicaea adopted the Nicene Creed which described Christ as “God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God, begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father”. The creed used the term homoousios (of one substance) to define the relationship between the Father and the Son. After more than fifty years of debate, homoousios was recognised as the hallmark of orthodoxy, and was further developed into the formula of “three persons, one being”.

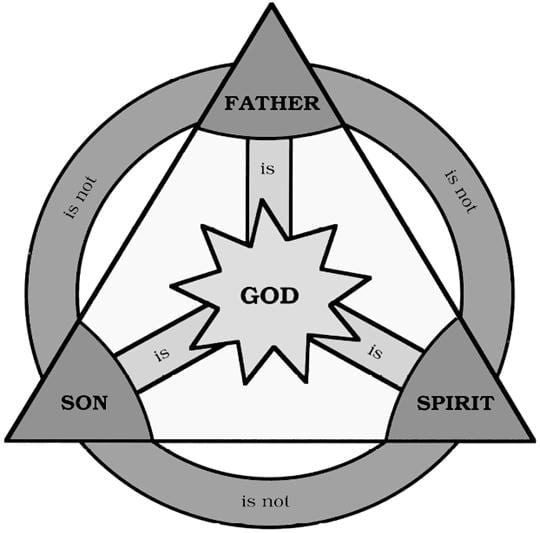

To me, this is just word salad. Williams pictures it like this:

He says, “Prima facie, trinitarianism looks like the claim that one plus one plus one equals one. This is what philosophers call ‘the logical problem of the Trinity’.” He is quick to point out that you cannot solve this by using the heresy of modalism, that God can’t just have three roles as Clark Kent might also be a journalist and superman and whatnot. Likewise, he states that you cannot solve the problem with polytheism such that there are multiple gods as separate entities within the single entity of the Godhead. There has to be some kind of “differentiated unity”.

Christians thus believe that there is one, and only one God and that this one God is a Trinity of divine persons. The Trinity (or ‘Godhead’) is one personal divine being (this is one sense of the term ‘God’) essentially composed of three divine persons (distinguished by different senses of the term ‘God’).

The crucial point here is that in our list of four propositions the term ‘God’ is ambiguous. If ‘God’ is understood in the very same sense in all four propositions, and we reject modalism, then they form an inconsistent set. However, the term ‘God’ has a range of meanings. Most obviously, ‘God’ can mean either ‘the Trinity’ or ‘a single divine person’. Hence while the proposition ‘There is only one God the Father’ means that ‘God’ as qualified by being ‘the Father’ is a single divine person, the proposition ‘There is only one God’ needn’t be read as meaning that there is only one divine person, but rather as meaning that there is only one Trinity of divine persons (only one of whom is ‘God the Father’).

This sounds an awful lot like the fallacy of equivocation by using different definitions of terms to hide a multitude of sins within an argument or thesis. Williams then opts for an analogy:

I like the musical analogy proposed by theologian Jeremy S. Begbie: A musical chord is essentially composed of three different notes (to be a chord all three notes must be present), namely the first, third and fifth notes of a given musical scale. For example, the chord of C major is composed of the notes C (the root of the chord), E (the third from the root) and G (the fifth from the root). Each individual note is ‘a sound’, and all three notes played together are likewise ‘a sound’. Hence a chord is essentially three sounds in one sound, or one sound essentially composed of three different sounds (each of which has an individual identity as well as a corporate identity). By analogy, God is three divine persons in one divine personal being, or one divine personal being essentially composed of three divine persons. Moreover, when middle C (the root of the chord) is played it ‘fills’ the entire ‘heard space’. When the E above middle C is played at the same time, that second note simultaneously ‘fills’ the whole of the ‘heard space’; yet one can still hear both notes distinctly. When the G above middle C is added as well, a complete chord exists; one sound composed of three distinct sounds.

Sadly enough for Williams is that this appears to be the main crux of his argument. After this, he boldly states:

So the doctrine of the Trinity isn’t self-contradictory, and there are some analogies that help us to conceptualise the Trinity.

This is a long article that he has written, but, from this point onwards, he starts arguing for the Trinity through history and theology that assume it makes coherent sense as an opening premise. But nowhere does he really properly establish the coherence of this concept past a mere analogy. And this analogy doesn’t work, anyway. Begbie’s musical analogy claim follows:

What could be more apt than to speak of the Trinity as a three-note-resonance of life, mutually indwelling, without mutual exclusion and yet without merger, each occupying the same ‘space,’ yet recognizably and irreducibly distinct, mutually enhancing and establishing each other?

Each of the separate sounds above cannot do what the other sounds do. They have their own properties as sounds and are mere composite parts of the final sound of the chord. Look, we have three entities that, when heard together, produce another entity to the listener. This is not analogous to the Godhead, because I don’t think anything is. Brad Broadhead explains in further detail:

Begbie’s question requires a little unpacking. He helpfully refers to musicologist Victor Zucherkandl on the major triad. Zucherkandl explains that hearing a triad does not admit juxtaposition; each note occupies an identical space simultaneously. And yet the presence of one tone in addition to another does not mask or alter the other; it “turns out to be, as it were, transparent for it.”39 He goes on to describe the notes as being heard through each other, interpenetrating, bringing to mind the Trinitarian conception of perichoresis.40 Perichoresis in relation to the Trinity as described by Pseudo-Cyril and John of Damascus necessitates that each member of the Trinity “ dynamically make room for, without in any way diminishing, the others.”41 Furthermore, just as Jesus talks about being in the Father and the Father being in him in John 10:38, when a note of a major triad is sounded the other two notes are present as resonating overtones or ‘simple difference notes’ even when they are undetected by the human ear.42 In a triad, there is room for each note which, far from diminishing the others, reinforces or enhances them. This ‘enhancement’ has a physical explanation: certain overtones inherent in each note overlap each other; these overlaps strengthen these overtones in a certain pattern which is picked up by the ear.43 This is why a small number of wind musicians playing a triad in tunecan produce a more powerful sound than many times their number playing the same triad who are not in tune. The Trinity operates as one, perfectly ‘in tune,’ with each member reinforcing the others in every activity. In answer to Begbie’s question, it is indeed difficult to conceive of another phenomenon in nature which so aptly illustrates the Trinity in terms of relationship in aspatial context.44

To me, this looks like modalism by another name. As C. Michael Patton explains of modalism:

- Modalism: The belief that God is one God who shows himself in three different ways, sometimes as the Father, sometimes the Son, and sometimes the Holy Spirit. It describes God in purely functional terms. When he is saving the world on the cross, he is called Jesus. When he is convicting the world of sin, he is called Holy Spirit, and when he is creating the world, he is called Father. The error here is that this is contrary to what we believe: one God who eternally exists in three persons, not modes of functionality. It is not one God with three names, but one God in three persons.

When C is played on its own, its function is to be heard like C, when E…and when they are played together, their function is to sound like the chord does. I really don’t see that this analogy does what Williams and others want it to. I mean, it sounds nice, but…

As the SEP sets out about a mode and modalism in the context of the Trinity:

But, what is a “mode”? It is a “way a thing is”, but that might mean several things. A “mode of X” might be

an intrinsic property of X (e.g., a power of X, an action of X)

a relation that X bears to some thing or things (e.g., X‘s loving itself, X‘s being greater than Y, X appearing wonderful to Y and to Z)

a state of affairs or event which includes X (e.g., X loving Y, it being the case that X is great)

These three notes separately and together, to me, have modal qualities. To refer back to what I previously said, C is no more the C major chord than E or G are. The SEP article is a very detailed analysis of the Trinity claims.

Furthermore, I think this also makes a mockery of divine simplicity. One entity doing the job of the musical chord is far simpler than three entities in relationship with each other, coming together to make a sound that is richer than their own sounds on their own. I mean, why?

Some people argue that using analogies works for different aspects of the Godhead:

It’s important to be specific about the nature of the analogy, and then perhaps to use a few to consider different aspects of the Trinity:

– water/ice/steam = considering the substance

– father/brother/uncle = considering roles/personae

– three-blade propeller = considering the inseparability

But this doesn’t really answer the issue that is the coherence of the idea of Trinity as a whole. This is almost like being modalist with your analogies! The idea with the chord analogy is that there is supposedly where one of the members of the Trinity isn’t. Not when the chord is seen as a whole, of course. But when you look at each individual note, they do not have the property of the chord as a whole. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts, which means that none of the parts on their own can be fully God.

Offering an analogy and saying, “well that sorts that one out, and anyone who disagrees is naive” is not good enough to leave one thinking that the Trinity is, indeed, coherent. When I mentioned the other day that I would really struggle to sleep at night thinking that a massive part of my philosophical worldview was problematic, and when I said I didn’t think any of the aspects of my worldview were indeed problematic, this is precisely what I mean. I think, for me, if I was a Christian, I would really struggle with my belief. I would struggle because the very heart of the Christian religion and so many denominations is to Godhead, the Holy Trinity. And it doesn’t work.

RELATED POSTS:

The Holy Trinity Is Incoherent #1

The Holy Trinity Is Incoherent #2 – Penal Substitution Theory

Stay in touch! Like A Tippling Philosopher on Facebook:

A Tippling Philosopher

You can also buy me a cuppa. Please… It justifies me continuing to do this!

TAGGED WITH: HOLY SPIRIT JESUS PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION THEOLOGY HOLY TRINITY PETER S. WILLIAMS THE TRINITY